Inside Scoop: How SDAFF chooses films

Film festivals are shrouded in mystery, and the lack of complete transparency, along with the sheer volume of annual submissions, have led some to doubt the legitimacy of the process. We can’t speak for other festivals, but we can certainly speak for ourselves. Here’s the chronology of a film submission at the San Diego Asian Film Festival office.

Arrival

At the height of our submissions period, we’re getting dozens of discs and online submissions a week, and each submission is carefully processed and filed by our interns. This year, the programming team has three interns, each selected for their ability to juggle large stacks of DVDs and input data into our database. Naturally, our competitive selection process is comprised of actual juggling – of apples, cell phones, and earrings once owned by Lee Ann Kim. Extra points are given to intern candidates who can juggle while typing. The formula used to assess intern suitability is (apples*2 + phones*3 + earrings*2)*(words/minute), and we have found that this scientific approach produces the most qualified interns.

Assessment

Interestingly, this formula is adaptable to our assessment process as well. All programmers are required to watch films from beginning to end, and not multitask while watching the screeners, so best to mimic the actual viewing experience in a movie theater. (More on this later.) But the initial screening process involves measuring intellectual engagement and physical response. While watching the films, programmers are required to log the number of times the film triggers in them: mental images of Jeremy Lin and Roger Ebert, unusual levels of salivation (food porn is always a winner), thoughts of their college Asian American Studies professor (for better or worse, because worse is always better), times they sang “oppa gangnam style” to themselves. These tallies are then inputted into the formula:

(((Lin/Ebert)+Salivation+(Professor*3)+Gangnam)/(Film’s running time))x(beats/minute)

whereby “beats/minute” refers to the programmer’s heart rate immediately at the start of the film’s credits, which is when 65% of moviegoers make their decision whether they “liked” a movie or not, according to a study between Stanford University and the New York Film Academy. The film running time is included to account for the fact that longer movies shouldn’t have an advantage over shorter films. Because it’s all about being fair.

After the first round of viewings, the programming team then has a numerical valuation of each film. Obviously, films cannot be reduced to numbers. (Because film is art.) This takes us to the next round of evaluation.

Argumentation

The top 80th percentile following the first round enter the qualitative phase, or as we call it internally, the wrestling phase. That is because it involves wrestling.

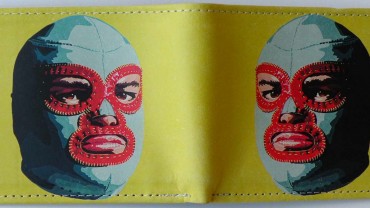

Many filmmakers make the incorrect assumption that when they fill out their home addresses in their film submissions forms, that it is because film festivals will send acceptance/rejection letters to those addresses. First of all, festivals are ultra-modern and only fulfill dreams/break hearts via email. But for us, addresses are essential because it allows programmers to, with the help of interns’ Google map skills and our airline sponsorship money, hide out in front of filmmakers homes and put them in headlocks and see if they scream for mercy, fight back, or pull out their lucha libre masks prepared for just this sort of occasion. Just as in filmmaking, it’s not about which choice you make, but what you do with it that counts. Consider this:

- Scream for mercy: a yelp or a gasp might imply a lack of confidence, whereas a maniacal scream might mean the filmmaker was so focused on what he/she had been doing (for instance looking for house keys) that any external trigger could lead to extraordinary panic. This shows attention, vision, and commitment, all factors that we value in filmmakers. We call this “making an argument.”

- Fight back: if they fight back, they better win. Period.

- Lucha Libre masks: for the programmer, this is always the most frightening moment, but also the most exhilarating — the sort of moment we fear but live for. It’s a kind of discovery: what color mask? What animals or warrior gods are evoked? What is the facial expression? One can learn much from a luchador’s mask, especially when it comes out of nowhere and rams into your face while you prepare for combat on the enemy’s lawn. You can learn a lot about a filmmaker from this sort of encounter. You can also learn a lot about yourself.

The wrestle (the “argumentation”) is filmed by a member of our Video Production Team, and returned to the office, along with any mementos from the fight (teeth, torn bits of clothing, wallets). This leads to the presentation of arguments, which comprises the bulk of our programming meetings. Programmers sit in front of large projection televisions from 1992, while each wrestle with filmmakers is screened.

To mimic the experience of every possible paying audience member, programmers are placed into a wide variety of mental states. One programmer may be forced to watch the clips after a long 10-hour day of work, to mimic the festival-goer looking for some post-work entertainment. Another programmer will be sleep deprived for 24 hours to mimic the festival-goer prone to falling asleep. Another programmer must watch under the influence of alcohol, another must be celibate for six months before the screening, another will have his/her phone ring every five minutes during the screening, etc. At the San Diego Asian Film Festival we believe in serving all members of our community, and this is reflected in the way we watch wrestling videos.

After the presentation of argument, the programmers go home to “sleep it off.” The next day, each programmer picks their favorite wrestling video given their mental/physical state. The names of the wrestlers are then matched with the films they originally submitted. Any wrestler/filmmaker with more than one vote is automatically in. Any wrestler/filmmaker with only one vote will have the name of his/her film placed in a large glass bowl and randomly selected by the winner of last year’s Grand Jury Award, in this year’s case, Dave Boyle.

Advertising

When our wounds heal and hangovers subside, the programming team re-watches the original submitted films and prepares a marketing plan for each. This involves selecting images to represent each film and writing program notes for the website and program booklet. The mementos from the wrestling matches, as well as the videos of the matches, are put into a large Trader Joe’s canvas bag and sacrificed at a bonfire at Ocean Beach, San Diego. This is the team’s way of pleasing the festival gods (or “Redford,” as he’s known on the circuit), as well as a way of “destroying the evidence.”

And then we’re left with 150+ films from over 20 countries representing the very best in Asian and Asian American cinema! We’ve been doing it for 13 years and it seems to be working. Congratulations to all of the filmmakers, and a special shout-out to our amazing team of programmers and interns, without whom this festival would not be possible!

Join the Conversation